A Garden Visit: Malus Farm

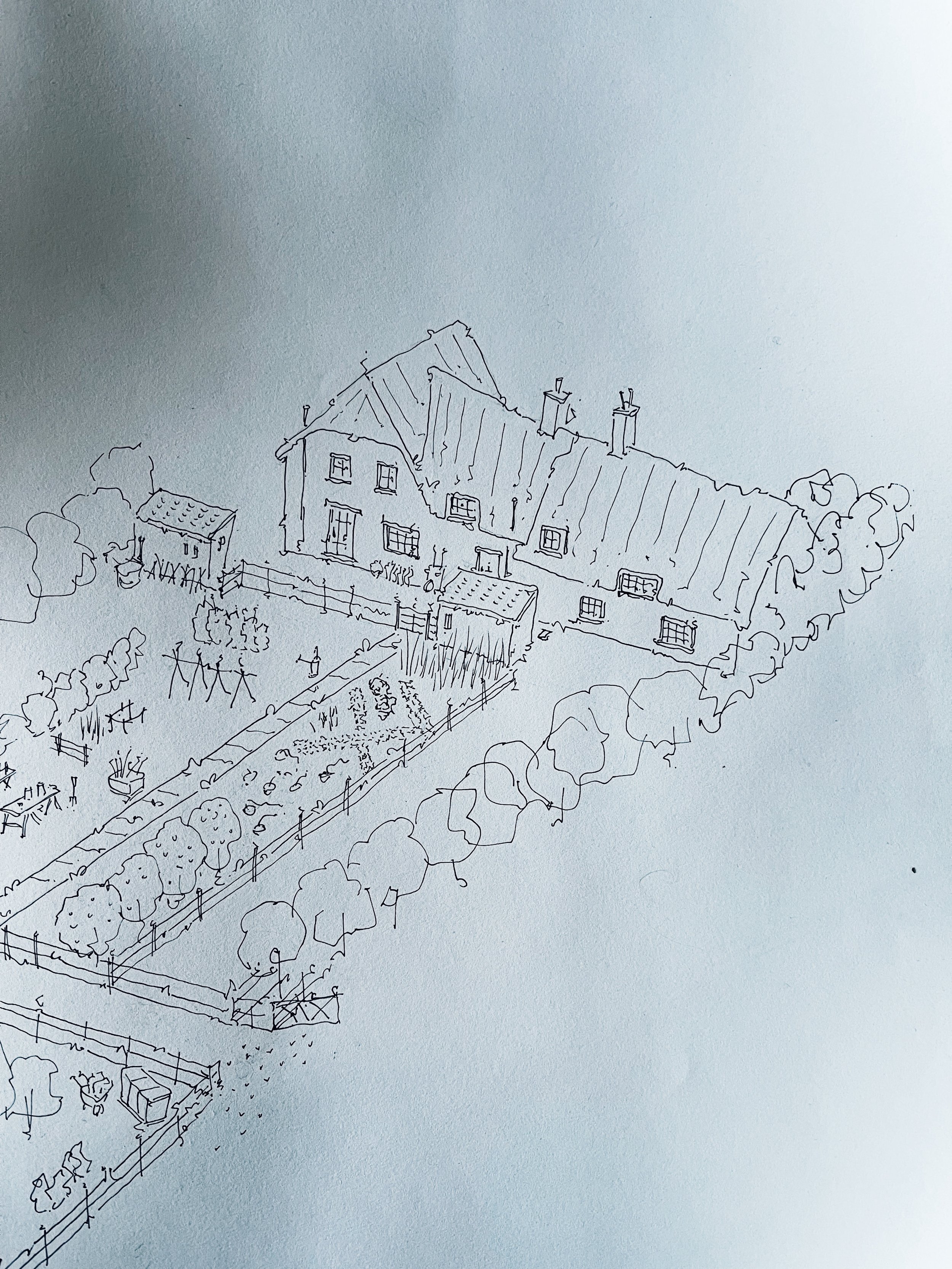

Illustration from ‘Grow & Gather’ by Rob Mackenzie

Most months, particularly in these glorious long, hot days of High Summer, I write to you about a garden visit. South Wood Farm, perhaps, or the Pythouse. A thinly veiled excuse to go and spend time admiring the fruits of the labours of others and, whilst Instagram and Gardens Illustrated is all very well, there is nothing more inspiring than moving around a garden of great beauty. I would go so far as to say, even moderate beauty. The practical trumps the digital in so many arenas of life.

Today, not only a tour of a garden that is closer to home, but one which does not technically yet exist. Its creation is inching ever closer and I may finally have started to allow myself to believe in hope. Our campaign to buy the cottage next door, along with its outdoor loo, south-facing wall, and long, shaded back garden, has been six years and counting, but we may finally be drawing towards its climax. I will not bore you with the details of the skirmishes and volleys that have formed the war of nerves because I have decided that, for closure and revenge, I shall turn the whole thing into a book. However, what you should know is that we are due to exchange in a fortnight, and oh hope of hopes, complete the day we return from our Cornish summer holiday.

My bedroom window & the adjoining house of my dreams

Nothing is certain until I have a key in one hand and a glass of champagne in the other but I have, of course, already knitted the two gardens together and conjured up their beauty in my mind. In fact, you may already have seen the garden; when Rob Mackenzie came to draw Malus Farm, we operated a little artistic licence and included all three of the cottages in the row, and not just my tiny two up, two down that nestles in the middle. Yes, this was very awkward when the neighbour borrowed a copy of the book (the fact that he wouldn’t give me the money or the satisfaction of paying for it tells you everything you need to know). He didn’t mention this when he gave it back, he was too swollen with smugness that he had found a typo in one of the last chapters, and so keen to let me know about it.

Technically. 1, 2 & 3 Chuch Cotts

But they do say, if you can see it, you can have it.

The illustration wasn’t the start of my dreaming; it was a natural response to believing so fully and truly that one day, Malus Farm would be a little bigger, a little more generous, a little more abundant. And have somewhere to sit in the evening. All gardens start in the mind, they do, by definition, mark the point of human endeavour and the natural world. Dreaming is an unmissable step in the otherwise quite pragmatic art of garden design.

In fact, some gardens only exist in the imagination. Winning the prize for my favourite book title ever, ‘The Most Beautiful Gardens Ever Written’ details the gardens of fiction. I found the contents of the book to be generally crashingly disappointing compared to the title, but that may have been because I don’t know the novels in which the gardens featured. Only one was familiar to me. ‘Alice in Wonderland’, and that was terribly rude about gardens. The flowers, being humanly manipulated, are humanly rude and mean to Alice. It is only when she goes into the wood, a representation of ‘real’ nature and therefore very different to the garden with the painted roses, does she forget her name and she and a fawn wander without fear of one another.

The disappointment that I felt on actually opening the book might be because I write better than I garden. Not day to day gardening (I am a dab hand at that), but the big gardening. The paths and the planting schemes, anticipating the final heights and positioning of trees, and the permanent decisions that, when someone who really knows what they are doing gets it right, you don’t see so much as feel. I hear Rousham is like that, and xxx certainly is. A human mind thought of this space, shaped what was there, what grew and what didn’t, and created a garden. There is a reason why architects make the best garden designers – they can think in three dimensions. Although gardens are even tricker, because plants grow and change over time, so you have to think in four.

I think in language, in words, not in shapes and images. Not just that, I think in ideas and emotions. My day job is to take incredibly complicated and abstract ideas and put them into words. I write reports that sum up a whole life in paragraphs and numbered sections. What I am saying is that I write better than I create, and the garden inside my head will rarely be wholly reflected by the garden on the ground. But what I lack in implementation, I make up for in ambition, and everything starts with a name.

Names are part of creativity and the act of creation. If you can name it, it exists. Not only that, but naming brings you into relationship with that thing. (This act does have connotations of power and so should be used lightly and thoughtfully. There is a reason why a bully’s first line of attack in name-calling.) I did not adore my Land Rover when I first bought her. I dreamt of accidentally driving her into a ditch and claiming the insurance. And then one day, I named her Margot, and I toppled headlong into love.

Puppers was Mary when she first arrived, but she didn’t feel like a Mary, so she was renamed Maud. (Top marks if you can name the Jilly Cooper novel.) She is never called Maud though; she remains, to this day, Puppers. She is now six.

Hugo was Jack when he arrived, the day after our wedding, wrapped with a bow. His full kennel name is Sandlauger Jack Frost. Within the hour, he was renamed Hugo. This is not a deep and meaningful psychological transition; I am simply too snobby to have a dog named jack. He is, every inch of him, a Hugo.

When I came to register the garden for organic transition, I had to think of a name. 2 Church Cotts is the house, not the ground, and doesn’t include 3 Church Cotts and its associated land grab . The deeds for the house don’t even cover beyond the end of the kitchen garden. Grace Alexander Flowers is me. The garden needed an identity of its own. It needed a name. Malus Farm.

Now it has a name, I can love it. I can think of it as ‘the farm as an organism’ (a biodynamic idea). A Gestalt. A whole that is greater than the sum of its parts. I was so absolutely convincing (and convinced) that Malus Farm existed as a thing, I even got the Post Office to recognise it, and deliver post to it.

[A huge thank you to Joanna Game for posting this to me. It meant more than you will ever know.]

To take it all a step further, I got Kristy Ramage in to talk about how to knit all the different rooms together, aesthetically and conceptually. It must have been the only time an internationally renowned garden designer has had to do a site visit by looking over a wall whilst pretending to look somewhere else entirely.

I may absolutely live to regret this, but we are starting to make plans for under the big sycamore tree (a wetland/pond area), the south facing side garden (an evening courtyard, screened from the road by pleached lime trees). My neighbour is expressing his deep resentment of me buying his house by hitting me where it hurts; his garden has been left to go to rack and ruin since the conveyancing got serious.

Consider these the before pictures for the most glorious transformation.

My tips on uniting a garden which might feel a little disparate and fractured

Emphasise the fractures and create rooms. These are simply areas of garden, often visually obscured from one to another, which fulfil a different role, or have a different ‘feel’. This can be as pragmatic as clustering all the boring bits (washing lines and children’s toys) into one ‘domestic’ area, and using another for growing food, and another for flowers. There can be a little overlap (violas amongst the carrots, red Russian kale in the flower borders) but don’t make it look like a small child has stirred everything together with a paintbrush. If you can, separate the rooms with some form of boundary. Trellises or screens with honeysuckle if you haven’t got the space (or the patience) for big hedges.

Sprawling gardens can be united with a common material. Bonus points if your uniting material is local or vernacular. (Mine is likely to be hazel, if that helps, but red brick if you have a red brick townhouse, oak if you have a manor house etc etc..) Arne Maynard wrote an entire book on this, Gardens With Atmosphere - Creating Gardens With A Sense Of Place. Out of print now, but I do recommend keeping an eye on eBay etc. But the punchline is the way to get gardens to sit lightly in their landscape is to ask the landscape what it would like the garden to look like. More genuinely useful tips in this article from Country Life.

Bear in mind that what you decide to put in can be as important as what you take out. Simon Dorrell, co-owner of Bryan’s Ground in Herefordshire, puts it succinctly:

‘Adhere to Arts-and-Crafts principles: observe and respect the local vernacular, use local materials and embrace Nature and you can’t go wrong.’

Keep your fingers and your toes crossed and, by the middle of the next month, there might be news…